This Isn’t an RPM: What’s Actually Going On With That Doubled Mintmark

You flipped a coin, scoped it, and your heart jumped. The mintmark looks doubled. You’re already imagining the PCGS label. Maybe an RPM. Maybe a DDO. Maybe payday.

Stop.

It’s machine doubling. And if it’s only on the mintmark, you can almost guarantee it. This isn’t a rare variety. It’s a mechanical hiccup, the coin-press equivalent of a drunk hiccup at last call. It looks flashy, but it means nothing.

Let’s break down why this happens, when mintmarks stopped being punched by hand, and how to spot the difference between actual mint errors and something that just looks cool under a scope.

Mintmarks Used to Matter More

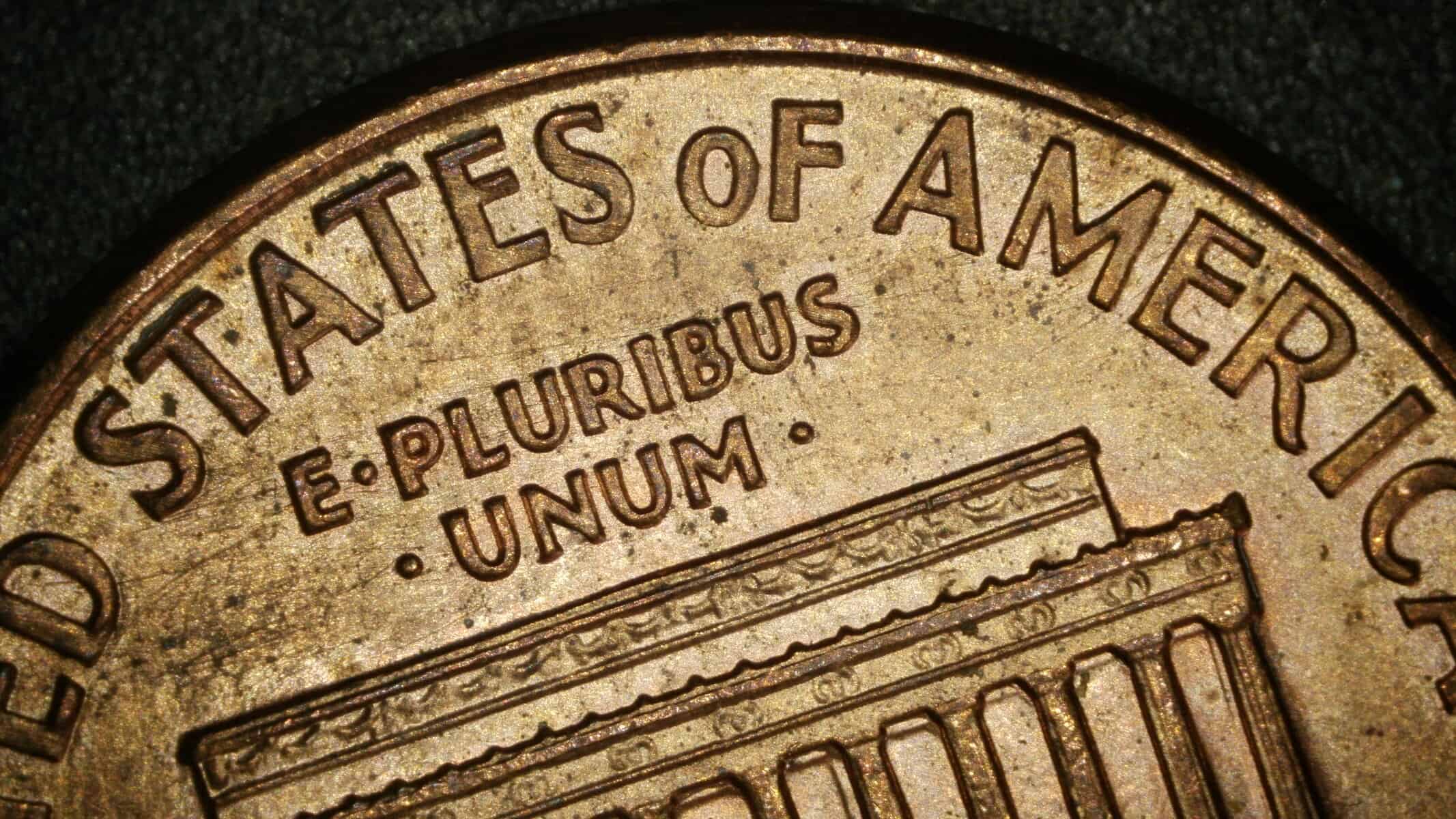

Looks dramatic. Isn’t. This kind of mintmark doubling is mechanical, not collectible, and definitely not an RPM.

There was a time when the little letter under the date meant something. Before 1990, mintmarks were added by hand to each working die. That meant real human error. Misplaced marks, rotated punches, doubled impressions. Stuff that actually changed the die itself, and that’s the kind of doubling collectors will pay for.

But in the 90s, the Mint wised up. They started adding mintmarks to the master die. That meant every working die from that hub came pre-loaded with the mintmark already there. Human hands were taken off the process. And with that, the chance for real RPMs (repunched mintmarks) pretty much vanished.

So if you’re holding a coin from the 2000s with a mintmark that looks doubled, here’s the brutal truth: it didn’t happen during hubbing or punching. It happened when the die slapped the blank. Mechanical error. Not collectible error.

Why It’s Always the Mintmark

If you’ve hunted rolls long enough, you’ve seen it. A ghost image clinging to the mintmark like it doesn’t want to leave the party. And it’s almost never anywhere else on the coin. Why?

Because that little letter is the highest, most delicate detail on the design. It’s the last part to strike and the first to get mangled when the press hiccups. The die shifts, the collar vibrates, the coin blinks and that crisp mintmark ends up looking like it had one too many.

Before 1990, mintmarks were hand-punched into each die, so you could find real RPMs. After 1990, it’s all part of the master design. No second punch means no repunch. So if you see doubling on a post-1990 mintmark, it’s just the machine twitching.

Not rare. Not collectible. Not even interesting, unless you’re writing a post like this one.

How to Spot the Difference

Here’s the brutal truth: most doubling you’ll see in the wild is worthless. But if you want to stop falling for machine doubling, burn these into your brain:

- Machine doubling looks flat and shelf-like. Real doubled dies have raised, rounded edges because they were struck that way from the start.

- MD slides sideways. It’s a mechanical shift after the strike. Doubled dies show full, separated design elements like a second outline or clear notching.

- MD is shallow and shimmery. It catches light weird but has no depth. A real DDO has weight to it, visually and physically. You can feel it, even if you don’t know why yet.

- It’s always in the same spots. MD loves mintmarks and date numbers. True doubling can show up anywhere on the design.

If you’re not sure, compare it to known varieties. Variety Vista, Wexler’s site, or even a quick Google search of “[year] DDO” will teach you fast. Or just bookmark this post and stop emailing coin YouTubers blurry screenshots.

Final Thoughts

Machine doubling is like junk mail for your eyeballs. It shows up constantly, looks like it might be something important, and ends up being worthless. Learn to spot it fast and move on. There’s better treasure out there.

If you’re serious about hunting down real varieties, learn what not to waste your time on. You’ll save yourself a lot of frustration, and your collection will be better for it.

Geoff runs Genuine Cents, a straight talking coin education project built from hands-on experience and hundreds of hours examining coins. He is an ANA member and writes practical guides for new and returning collectors who want clarity instead of hype. If you want to reach him, message him on Instagram at @GenuineCents.