Grease Filled Dies: Why Your Coin Looks Half-Faded

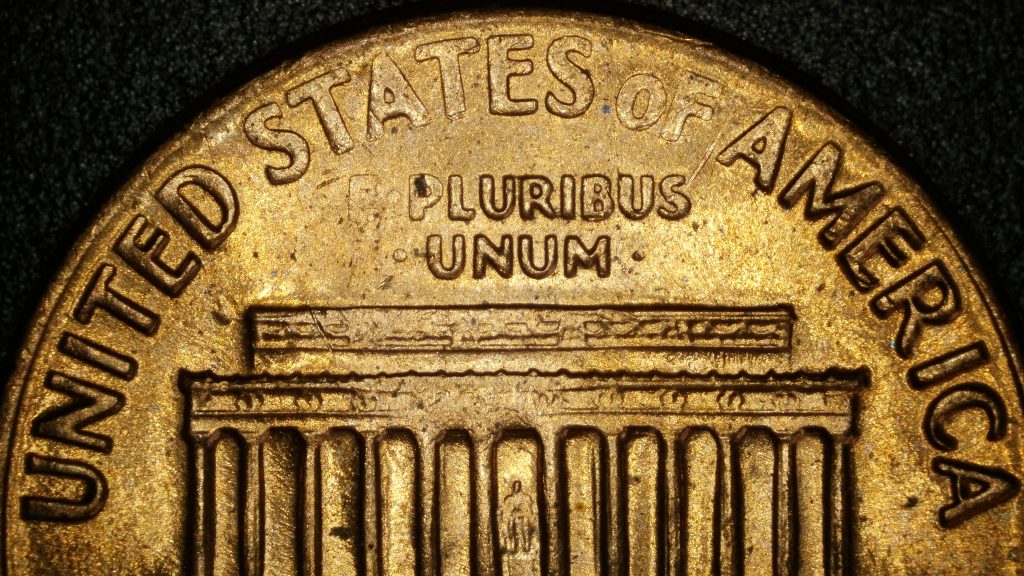

Grease filled die on a 1972 S. The Mint basically sneezed on the die and the coin paid the price. Soft, missing detail, classic look. Not valuable, still cool.

When a coin looks weak or washed out in random places, most people think it’s worn down. Sometimes they’re right. Sometimes they’re not even close.

This is a grease filled die. It happens when mint machinery gets clogged with thick gunk made of metal shavings, old oil, and debris. That paste fills the recessed parts of the die and blocks metal from flowing into certain details during the strike. The coin ends up with soft or missing areas while the rest looks normal.

Your coin is technically under-struck in those spots, but the important details were never struck in the first place. That’s why grease fill can look sharp and crisp around the edges but ghosted in a single word or design element.

What to Look For

- Random weak or missing letters

- Patchy fading, not uniform wear

- No flattening across the coin (which real wear produces)

- Normal rims and devices in unaffected areas

- No doubling or distortion

- No signs of post-mint damage

Why It Happens

1999 Jefferson nickel struck through grease. Parts of IN GOD are missing and the jawline is soft because the die was clogged when this coin was struck.

Grease filled dies are a side effect of how fast the Mint runs coin presses. Each strike generates heat, vibration, metal dust, and shaved fragments of planchets. Over time, all of that interacts with the lubricants inside the press.

Inside every high-speed coining press, there are three things constantly being produced:

- Metal dust from repeated strikes Every time a planchet is struck, tiny amounts of copper (or the outer copper plating on zinc) shear off inside the chamber. It’s microscopic, but millions of strikes per day produce a surprising amount of powder.

- Oil and grease from the press itself Dies move up and down at incredible speed and require constant lubrication. As the press heats up, that lubrication thins, spreads, and mixes with surrounding debris.

- Stray particulate from the feed system Feed fingers, conveyors, and planchets themselves shed tiny amounts of dust, plating flakes, and grime.

All three of these combine into a sticky paste that the Mint calls die fill or struck-through debris. When enough of this sludge builds up, it eventually settles into the low points of the die. Those low points are the places that create raised details on the coin: letters, numbers, small design devices, and fine relief.

Once the debris is packed in tight enough, it blocks metal from flowing fully into those spots during the strike. The result is a coin where the design is incomplete even though the strike pressure was normal.

A few extra things that matter:

- The highest points of the die clog first On a Lincoln reverse, letters like E, PLURIBUS, and UNUM tend to fade before the building because those recesses are shallower and easier to fill.

- The press does not stop immediately when die fill starts A press operator may run tens of thousands of coins before noticing, especially if the fill is mild or localized.

- The die can “self-clear” temporarily A fresh planchet hitting the die just right can knock out some of the packed grease, which is why grease errors can appear in waves: strong → weak → strong again.

- Die fill does not change the metal on the coin Since the design was never struck into those areas, the fade will not show wear patterns. It’s “missing,” not “worn.”

- The effect depends on the gunk’s composition Thin grease causes light softness. Thick packed sludge creates missing letters, lost serifs, and sometimes entire devices disappearing.

This is why a grease filled die can look so dramatic even on a well-struck coin. The force of the hammer die is still there, but the details never make contact with metal because the recess is literally clogged.

Are Grease Filled Dies Worth Anything

Most grease filled die coins have no real market value. They are not rare, they are not dramatic enough for premium collectors, and they show up frequently in circulation. Even strong examples usually top out at pocket change unless the missing detail is extreme or visually interesting in a way that stands out immediately.

That said, they are still worth saving if you are learning. They are great for training your eye, posting comparison photos, and building confidence with basic error recognition. Think of them as practice reps, not portfolio pieces.

Close Out

Grease filled dies are simple, common, and usually not worth selling, but they show a side of the minting process that most collectors never think about. They remind you that coins are made on real heavy machinery that wears down, heats up, shakes loose, and keeps broadcasting those tiny problems onto billions of coins every year.

Save the ones that show the effect clearly, use them to sharpen your skills, and keep building that mental library of what real mint errors look like. Every one of these helps you get faster, sharper, and more confident with everything else you hunt for.

Geoff runs Genuine Cents, a straight talking coin education project built from hands-on experience and hundreds of hours examining coins. He is an ANA member and writes practical guides for new and returning collectors who want clarity instead of hype. If you want to reach him, message him on Instagram at @GenuineCents.